Quantum Untangled - How to make money from quantum computing in 2023

Commercialisation begins in the cloud

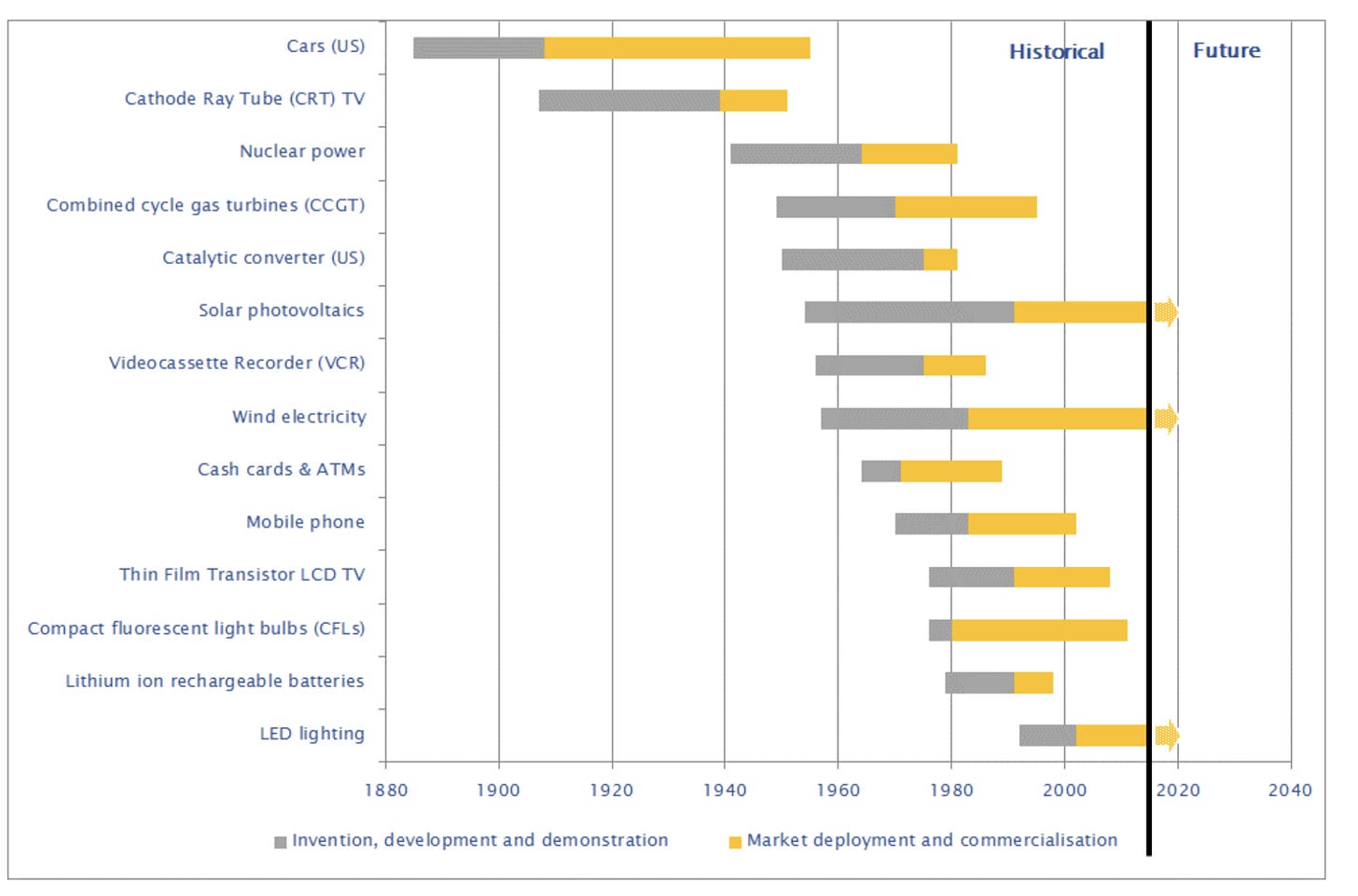

The average time it takes for a new innovation to become a widespread technology is 39 years. That number comes from a 2015 review of dozens of innovations and their path to commercialisation — everything from lithium ion batteries – a speedy 19 years to widespread market penetration – through to cars, which took a 70 years for the planet to get truly comfortable with.

Quantum computing is older than me - just. I was born in 1981, soon after CERN made its first proton-antiproton beam collision. Actually building a working prototype of a quantum computer took almost two more decades, with the first functional quantum computer coming online in 1998 and the first example of quantum commercialisation coming from D-Wave in 2011.

The study was published in the journal Energy Policy, finding the rate of mainstream adoption appears to be speeding up with each new technology.

Now, of course, there are entire conferences dedicated to the commercialisation of quantum technologies. The biggest companies and earlier players in the space are also claiming “commercial advantage” is on the horizon. IBM promises quantum advantage by 2026 and a number of investment funds and venture capital firms are now dedicated to the quantum space. But how do you actually make money from such a nascent technology?

One is by worrying about security. Quantum computers promise to break encryption as we know it, naturally creating a market for algorithms capable of withstanding the computational force of these exotic machines. Not only are standards in the process of being devised by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST to the initiated), but a whole new crop of post-quantum encryption services are sprouting from big tech and plucky startups alike, offering companies concrete means of armouring their systems before quantum hackers come along and metaphorically strip them naked.

Then there’s the cloud. Quantum computing’s core market proposition is that it helps solve incredibly niche, incredibly complicated problems much more efficiently than classical computing. Making that accessible to as wide a marketplace as possible means building the kind of infrastructure that houses a quantum computer in one place and allows multiple firms to access it remotely. Enter quantum-as-a-service (or QaaS, if you’re really down with the kids.) Big tech companies dabbling in quantum are already offering tailor-made access to proprietary quantum cloud services, liaising constantly with customers to hone their offerings and bring new quantum solutions to market.

“The cloud reduces the risk for companies in going to market, particularly in quantum,” Stuart Woods, a veteran of deep tech investment, and the recently appointed chief operating and strategy officer for UK-based quantum specific venture capital firm Quantum Exponential, told me on Friday 12th May. He’s not alone in thinking this. IBM has invested heavily in its quantum cloud, while Google Cloud, Azure and AWS also provide quantum hardware through cloud dashboards or Python modules.

But while cloud is a good option for many users and a great way to test algorithms, it does have some drawbacks.

For one thing, there’s no knowing where the quantum computer you’re tapping into is actually located. Often the hardware you want to use - be it a photonic quantum computer from ORCA or a superconducting qubit machine from IBM - won’t be in your country. This raises the problem of transferring data across borders and dealing with issues around GDPR and compliance. It means that if a developer working for one of the large banks wants to trial a new algorithm on quantum hardware they have to use synthetic data, as often the transfer of unmediated, un-anonymised data will be either legally impermissible or not viable for testing.

Woods says large data centre providers like Equinix are starting to realise the benefits of having quantum hardware on-site - not just for co-location and hybrid purposes, but also because it means data doesn’t have to be transferred outside of the building, let alone to another country. “That is what happened over the past four months, and that is where I think things will evolve,” said Woods.

It is still very early in the life cycle of quantum. The technology didn’t exist 43 years ago. There was no hardware until 25 years ago, and the first evidence of supremacy - doing something not possible with classical computers - wasn’t demonstrated until four years ago by Google.

The IBM roadmap to its quantum dreams

Will all data centres have at least one quantum computer by 2026 when IBM promises the first quantum advantage? Unlikely, but I think in that time frame we will begin to see so many announcements of data centres installing quantum hardware that it will no longer be newsworthy.

Tech Monitor aims to provide an essential resource for the world's top CIOs, business technology leaders and the tech-curious in a time of dramatic digital transformation. We are here to help you collaborate, innovate and connect.